Well. What a month, eh? I’ve now added a category of posts called ‘Trans Rights’. I imagine we’ll be seeing more blog posts about those in the future.

But for now, here’s some good news. In March, The Queer Natures project team met in person, further fortifying our ideas and practices. I’ve also got some updates regarding my poetry and about Our Transcapes. But the best news of all…? Read below!

The Sun shows some love

I’m delighted to announce that Queer Natures has received a very flattering accolade from The Sun newspaper. They mentioned our work with grace, noting the value in recognising the rich interconnectedness between all beings. I couldn’t be more proud.

My favourite bit:

£8 billion a year is earmarked for UK Research and Innovation grants … but millions was frittered on woke projects. “Brits know government waste is rampant — but this takes the cake!”

But, Sir: was it vegan cake?

Don’t give them the clicks – read a screenshot here (PDF, 345 KB).

Queer Natures retreat

The Queer Natures team spent three days together in Devon in March, trialling one another’s projects and learning about responsible facilitation, interrogating the meanings of ‘queer’, and sharing vulnerabilities, stories and learnings as we went. It was an incredibly inspiring retreat.

Dr Ina Linge brought us together at Dartington Hall, a space that has seen much art and education. Our project producers and supporters from Flock Southwest and Exeter University joined us, as well as guest speakers. I learned a great deal from everyone, and felt a great deal, too!

My fellow artist in residence, Siân Docksey, offered so much in her workshop. I never thought I’d voluntarily do pole dancing, least of all in front of people I know! But she handled my nerves with confidence, warmth and kindness, giving me the courage to go for it. In return, I experienced a new, freeing embodiment that challenged my own gender assumptions and allowed me to reconnect with my “soft animal body“.

It was bittersweet, dialoguing with my body for the first time since being chronically ill. The retreat gave me that gift, and I thoroughly recommend Siân’s pole dancing classes for anyone struggling with loving self-embodiment, in whatever way that shows up for you.

Our Transcapes

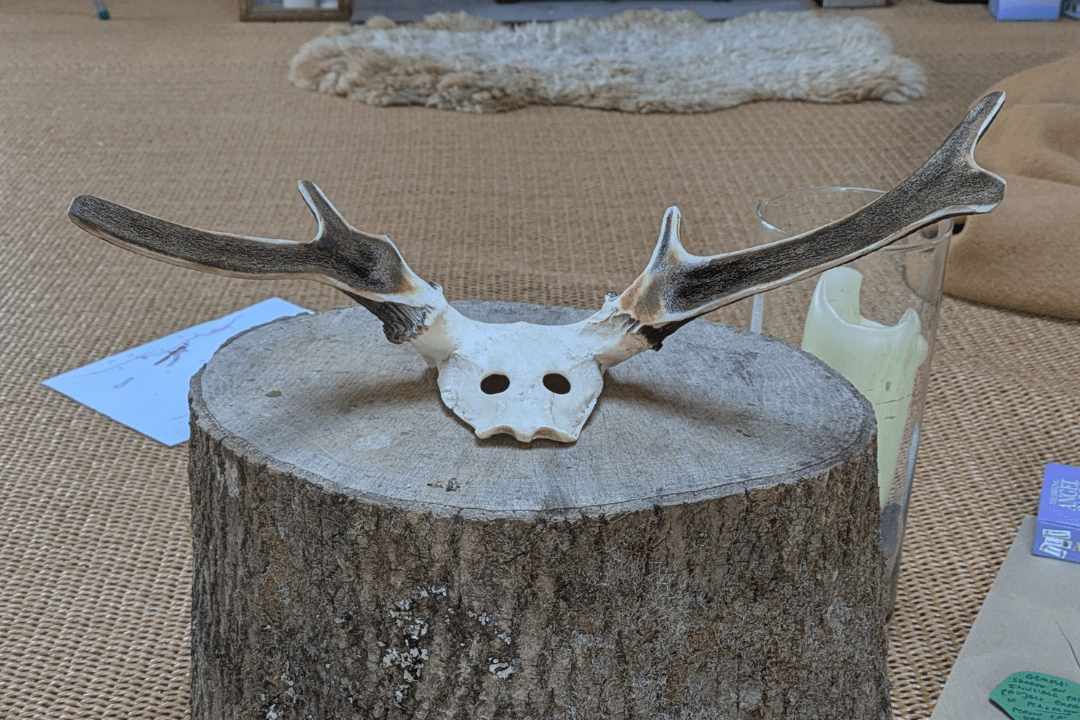

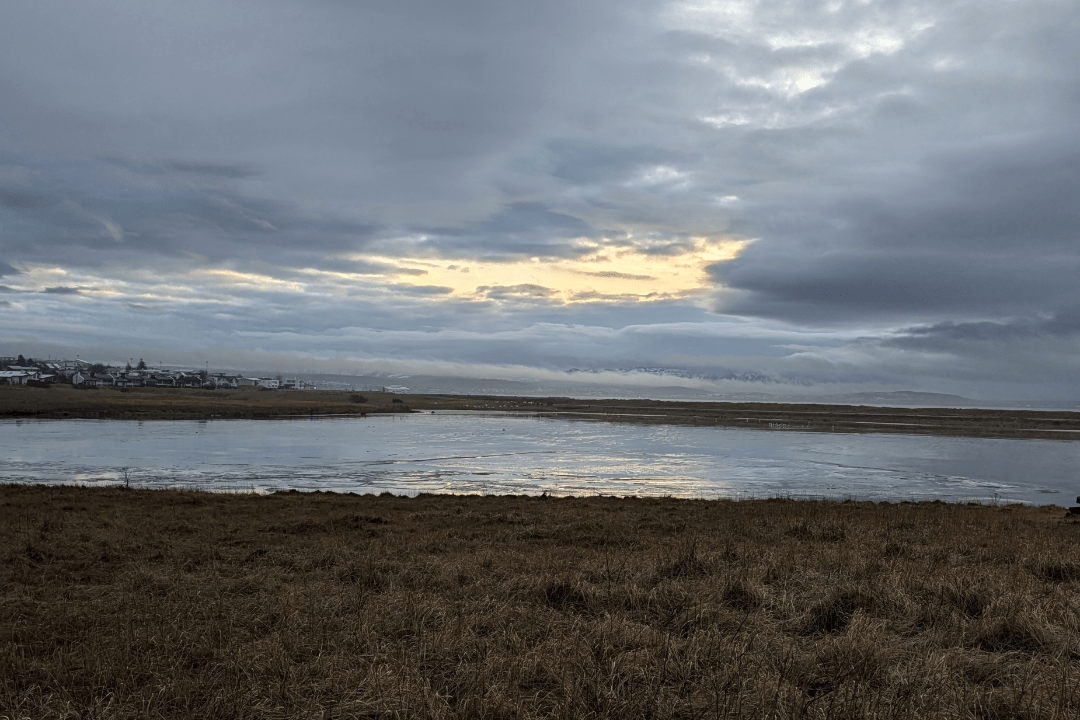

The retreat ended with my first run through of Our Transcapes. We headed out to the Devonshire countryside, explored water-bodies and wooded vistas, and shared stories of prehistoric non-dualities found in these lands. We then took part in a creative exploration activity around our own relationships with gender through a creative dialogue with prehistoric ‘queer’ artefacts.

While Our Transcapes is typically aimed at trans* participants, our project team is made up of folks who are across the LGBTQ+ spectrum, including trans* people. This offered me greater insights into the various different interpretations and experiences the project can offer. The project team offered very helpful feedback, both as participants and experienced facilitators. I’ve now adjusted the project for the autumn, when I collaborate with Peak Queer Adventures.

Some lovely feedback from a participant:

“Hugely positive and empowering! I felt the themes were held really sensitively

and with care, and S.K. is clearly an expert in this material and loved sharing

it 🙂I loved how “in nature” this event was too and broken up between more

communicative and more introspective sections – having a moment where we

were invited to be quiet and just connect with the outdoors was great.”

Before that though, this summer, Dr Ina Linge and I will head to the University of Galway Association for the Study of Literature and Environment’s Biennial Conference to speak about Queer Natures and Our Transcapes. Very exciting stuff – especially as the west coast of Ireland is bog city. I can’t wait!

Poetry as protest

As mentioned earlier, this past month has been hell for trans* folks, especially trans women. Sheffield held a superb protest after the Supreme Court’s ruling, which has effectively backtracked on 20 years of social progress by reducing women to their biological frameworks. As a result, trans people are no longer politically recognised as their gender. Allies across the city joined us for the protest – almost 1,000 people. Many of us cried. But we also loved. And we don’t give up.

Finding courage in my fury, I read my poem, ‘the curlews cry’ to the crowd. The poem explores my own relationship with my body, the interconnectedness between all beings, and how dangerous divisive narratives are, whether they be racist, sexist or transphobic. ‘the curlews cry’ has also recently been published in the wonderful literary and art publication, Seedlings: Winter. Find their lovely work here.

“The bog is in me”

Leaning into just how much I relate to bogs these days, I recently produced my first visual arts piece in a very long time. It was wonderful to reconnect with an artform I haven’t touched for years.

One upside to being chronically ill is my increasing resilience when it comes to sharing and creating works with less fear. I am grateful for that, even if I can’t do as much as I used to. Let’s see what the rest of this year brings.

As organisations are advised to segregate trans people from single-sex spaces, I refuse to be so divisive. I send all of you love. Yes, even you, The Sun editors.

Over and out,

S. K.